LOGISTICS RESEARCH

By Virginia Fani, Ilaria Bucci, Romeo Bandinelli and Elias Ribeiro da Silva

Logistics plays a key role in the supply chain by measuring businesses’ service levels. While the optimisation of forward logistics is a well-known practice, reverse logistics (RL) is too often overlooked. Traditional supply chains do not usually accommodate RL efficiently, and this oversight can dramatically affect sustainability and consumer satisfaction in industries such as fashion. Nowadays, especially in e-commerce, businesses must deal with products returned by customers. Combining clothing, shoes, jewellery and accessories reveals that 76% of online returns belong to the fashion industry.

The RL operations that most impact supply chains comprise returns from end consumers to manufacturers. RL is necessary to guarantee end customers the service levels they expect, particularly in the luxury sector. However, it can increase greenhouse gas emissions and pollution. Thus, optimising returns presents challenges regarding the location of supply chain nodes.

Evaluating centralisation and decentralisation strategies is crucial, as is defining hybrid configurations for RL that combine the two approaches. Distribution network design can support eco-friendly goals since these choices impact the environmental footprint of global supply chains. Therefore, our first research question was: How does distribution network design play a role in the sustainability of RL?

Distribution network design can support eco-friendly goals since these choices impact the environmental footprint of global supply chains

Sustainable goals cannot be the sole target in RL. Businesses must manage return processes quickly and cost-effectively. While green logistics practices typically go hand-in-hand with efficient solutions, shortening lead time goes in the opposite direction. To bridge this gap, we proposed employing simulation modelling as a tool to explore the trade-offs between environmental impact and service level. The way businesses handle returns could directly affect how customers feel about the company.

As industries continue to struggle with balancing operational efficiency against environmental considerations, our second research question was: How could trade-offs between lead time and carbon footprint be managed?

The role of RL in fashion

The fashion industry is known for its fast pace and constantly changing trends. In recent years, the detrimental impact of the linear fashion model — which follows a “take-make-dispose” approach — has become more evident. As a result, the integral role of reverse logistics has gained prominence within the circular economy framework.

RL stands as one of the five essential supply chain processes, along with sourcing, warehousing, manufacturing and distribution. Consequently, fashion brands must adopt a strategic approach to RL, carefully balancing environmental, economic and social considerations. To address these challenges, simulation emerges as a pivotal tool for optimising RL operations and allocating resources. Returns pose a challenge for organisations in predicting demand due to uncertainty in both the quantity and quality of these products, significantly affecting scheduling and inventory management.

Returns pose a challenge for organisations in predicting demand due to uncertainty in both the quantity and quality of these products, significantly affecting scheduling and inventory management

Case study: A renowned Italian luxury brand

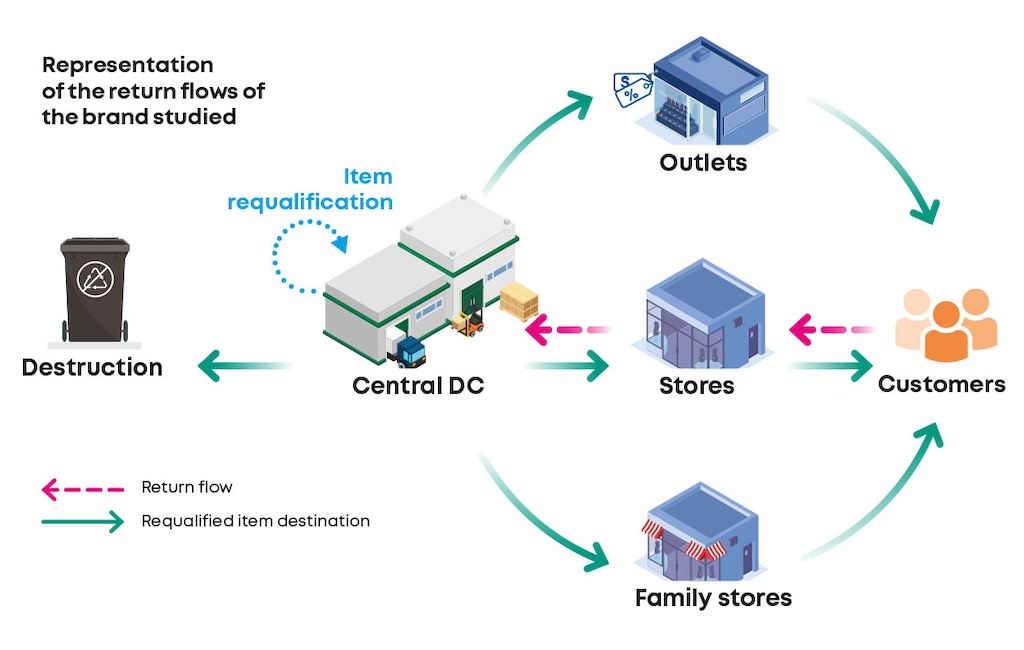

The company chosen for our research is an esteemed luxury fashion brand. Based in Italy, it has implemented a centralised returns system, and its operations are managed within a well-structured three-tier supply chain. This includes a central distribution centre (DC) in Italy, 10 local warehouses and stores, five outlets and a diverse clientele. All the facilities are strategically located in various countries spanning all five continents. The company handles a wide array of products, including apparel, bags, shoes, jewellery and accessories.

The RL process begins with the customer service department, which selects the type of return for each item. The company divides these products into four categories:

- Jewellery – full price (0.1%)

- Jewellery – markdown (4.3%)

- Non-jewellery – full price (1.7%)

- Non-jewellery – markdown (93.9%)

Full-price returns are resold at the original list price, whereas markdowns are products that have lost value. This phase also specifies the reconditioning process the merchandise will undergo, which determines the type of inspection it will be subject to upon arrival at the central DC for requalification. The process ensures that these items are directed to the appropriate channels, thereby enhancing the efficiency and reducing the carbon footprint of RL operations. The return process — including shipment — can be initiated from a store or a local warehouse. Subsequently, the products are transported to the central DC before reaching their final destination.

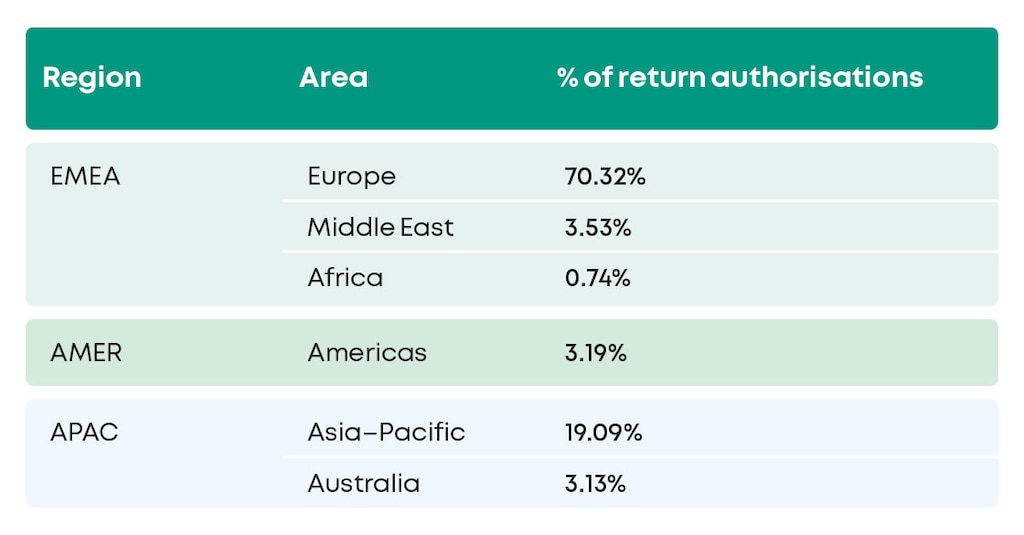

Our research focused on managed and authorised return requests, with demand originating from diverse countries. Europe, the Middle East and Africa (EMEA) accounted for 78.59%, the Asia–Pacific (APAC) region represented 18.22% and the Americas made up just 3.19%. Returns from the two largest markets, EMEA and APAC, are managed at the central DC in Italy. Nevertheless, the system could be optimised with a more sustainable network.

Simulation conditions

Simulation has been used to analyse complex supply chains and, recently, to identify network design strategies for increasing their sustainability. This scenario leveraged data from 18 months, ranging from January 2022 to June 2023 and divided by location.

Number of return authorisations by area

After the requalification process, products could have one of four destinations: store (when they could be sold for the same price as a new item), outlets (when they had lost value but were still sellable at a reduced price), family stores (when they had flaws but could still be sold in these establishments), or destruction (reserved for goods with severe defects that prevented their sale). Garments with no damages but from previous collections could also lose value and thus be sold at a markdown. This is one of the reasons why shortening lead time is very important. Additionally, a minor part of production could be allocated to stores or outlets to offset demand.

In line with the company’s current strategy, the following data were used to make assumptions:

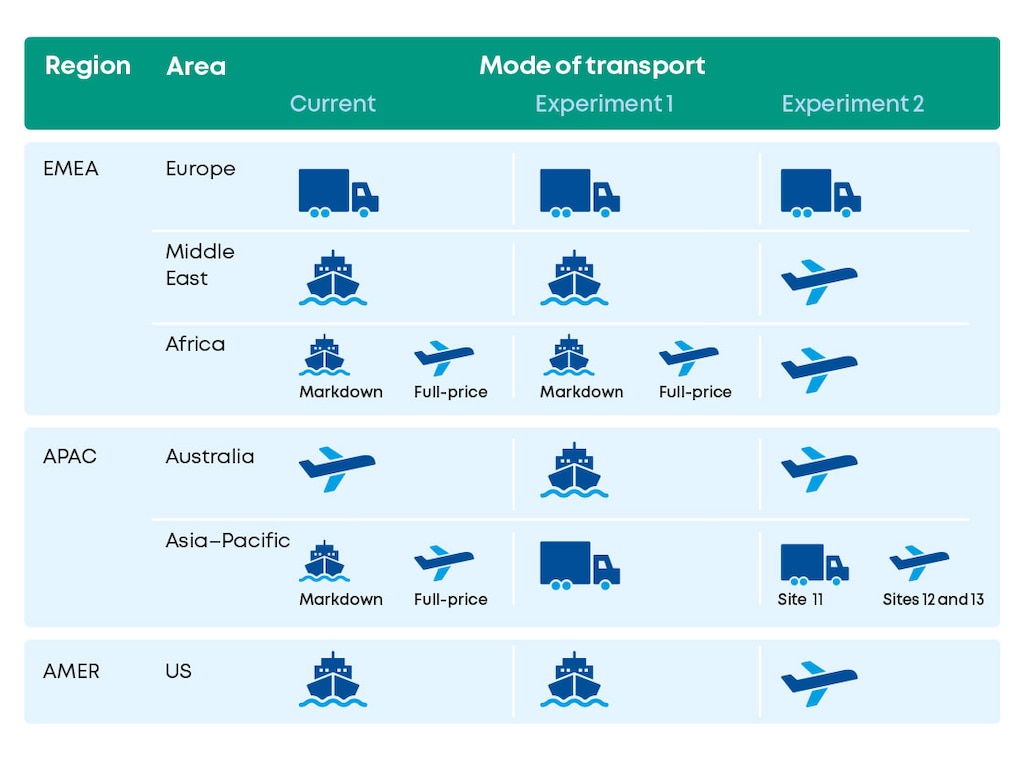

- Three transport modes were employed: truck, ferry and aeroplane. Their usage depended on the product’s added value and was governed by a minimum order size.

- Transport emissions did not include those related to loading/unloading operations.

- Replenishment was triggered either when a minimum number of items had been shipped by the end of the day or every three days, whichever came first.

- The vehicle selected depended on the route and type of product.

Experiments and results

We proposed two scenarios for this case study. Firstly, we analysed how the decentralisation of items’ requalification processes influenced the lead time and carbon footprint of the reverse flow. Secondly, we studied the effects of changing transport modes in critical routes.

Supply chain network and modes of transport per scenario

Currently, product requalification is only performed at the central DC. In Experiment 1, we investigated how performing this requalification in selected stores affected lead time, the number of shipments and the carbon footprint of RL. Given that Asia–Pacific represents the second highest percentage of returns, the strategic location of a new requalification centre in APAC was proposed.

Our results suggest that strategic decentralisation is a viable approach to balancing lead time and sustainability

Building on the decentralisation of return flows from the first experiment, the second scenario explored an alternative distribution strategy aimed at reducing lead time. We eliminated water transport, the most time-consuming mode. Instead, we studied the use of road transport for the RL flow to Site 11, near the new requalification centre in the APAC region. All other returns were handled by air transport.

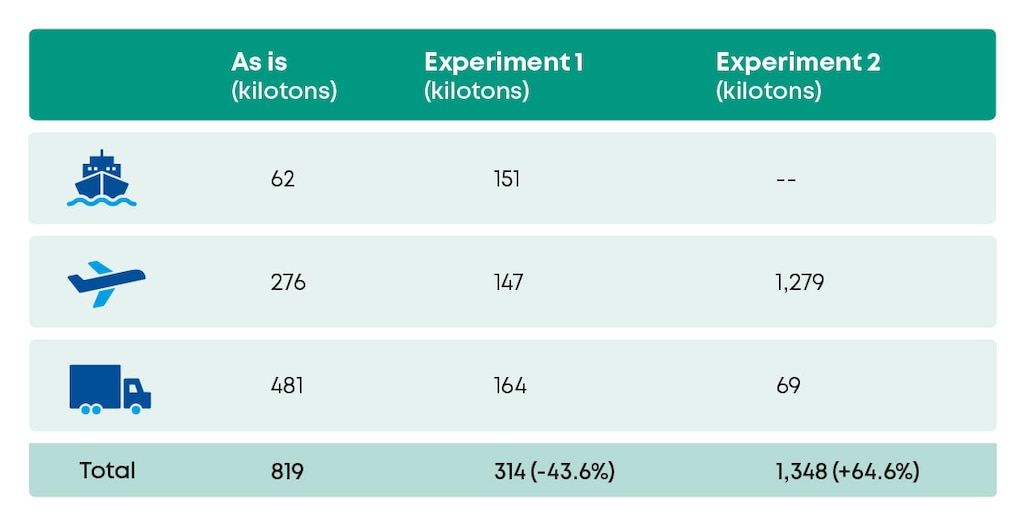

In terms of total CO2 emissions, Experiment 1 demonstrated a 43.6% reduction, suggesting that a more localised distribution of requalification activities can positively impact environmental sustainability. On the other hand, Experiment 2 showed a 64.6% increase in emissions due to a greater reliance on air transport.

CO2 emissions by scenario

While lead time was reduced in both cases, these findings highlight the need for companies to weigh the benefits of fast deliveries against the environmental impacts of increased carbon emissions. Our results suggest that strategic decentralisation is a viable approach to balancing lead time and sustainability, whereas changes in transport methods may not always achieve this outcome.

AUTHORS OF THE RESEARCH:

- Virginia Fani. Professor, Department of Industrial Engineering, University of Florence (Italy).

- Ilaria Bucci. PhD Student, Industrial Engineering and Philosophy, Department of Industrial Engineering, University of Florence (Italy).

- Romeo Bandinelli. Associate Professor, Department of Industrial Engineering, University of Florence (Italy).

- Elias Ribeiro da Silva. Associate Professor, Department of Technology and Innovation, University of Southern Denmark (Denmark).

Original publication:

Fani, Virginia, Bucci, Ilaria, Bandinelli, Roberto, Ribeiro da Silva, Elias. 2024. “Sustainable Reverse Logistics Network Design Using Simulation: Insights from the Fashion Industry”. Cleaner Logistics and Supply Chain 14 (Elsevier).

© 2024 The Authors. Licensed under CC BY 4.0, Attribution 4.0 International