In their book Flow: how the best supply chains thrive, experts Rob Handfield and Tom Linton link the success of supply chains with their ability to flow, a concept closely tied to the properties of nature. Applying these principles, they explore the impact of physics on global market policies, offering advice and strategies for optimising any supply chain or company.

Velocity, a function of time and distance, is one of many time vectors that is of interest to physicists. In physics, the ability to increase velocity will affect any number of desired outcomes. The same is true for supply chain outcomes. The fact is, doing anything faster is generally better because there are relatively few downsides to increasing the speed of movement of materials or completion of services in supply chains. This universal concept has become central to many executive boardroom discussions that focus on financial outcomes, many of which are related to improved velocity. Think of the following financial flows that are velocity-related:

- Many global supply chains focus on working capital (as opposed to profit margin) as a key measure of performance. Working capital is the most obvious outcome of increased velocity of a company’s financial flow as cash flow speeds up over time.

- Improving asset velocity, and specifically ensuring that inventory is constantly moving, is critical to a healthy supply chain.

- Velocity of planning and execution can produce improved outcomes, including better customer service, increased inventory returns, greater agility in response to change and quicker reaction time to supply chain disruptions.

- Velocity of decision-making in the face of major supply chain disruptions can significantly reduce their impact, as acting quickly based on real-time information can mitigate potential disasters.

A company’s ability to act fast based on early notification of events is critical to creating an important organisational resource for the future: supply chain immunity. We define supply chain immunity as the capability of an organisation to detect changes in its ecosystem, recognise the shift in conditions and respond in an agile manner to accommodate these shifts. However, many of us working in supply chains have noticed that it is not enough to know where the disruption is occurring; it is essential to know what to do in an emergency.

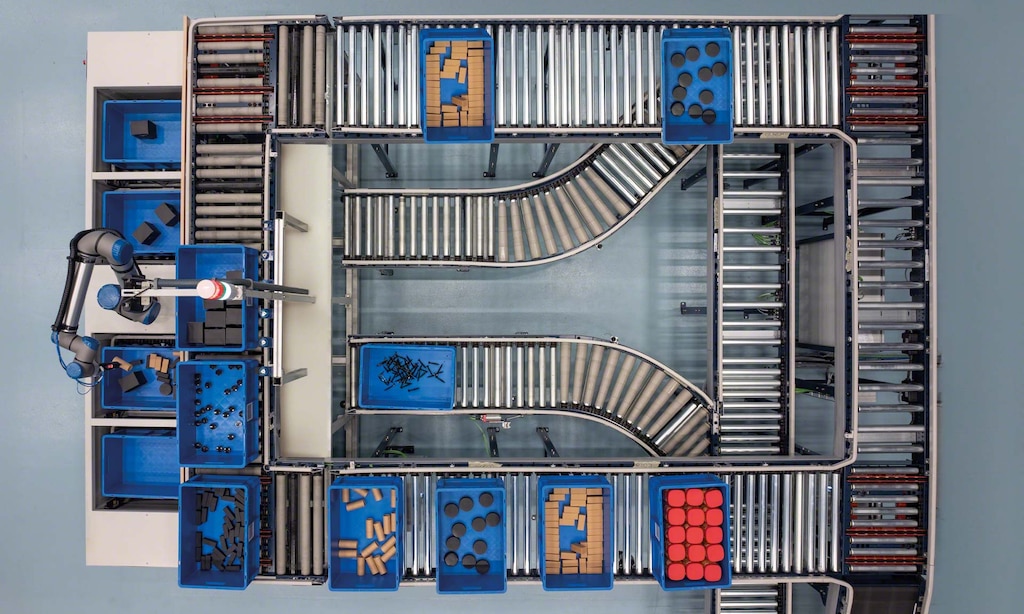

Ensuring that inventory is constantly moving is critical to a healthy supply chain

What this means is having a playbook that presents a plan for how to respond, that provides guidelines for people to follow when something unexpected happens. It should be general enough to cover any potential threat. We also need to know how to minimise the potential effects of supply chain failures from shutting us down should a major global event like a pandemic affect us. What we need is a plan for ongoing and persistent immunity. Two of the primary requirements for supply chain immunity are visibility and velocity.

Improving asset velocity – material flows over time

Moving goods quickly through a supply chain and making rapid decisions based on quick responses surely sounds desirable and, as we have noted, can provide increased immunity to shocks in the ecosystem. But what prevents organisations from doing more of this? As it turns out, three company actions are critical to successful inventory velocity:

- Assigning responsibility for generating material from the outset of a product’s life cycle.

- Designing products for life cycle management considering how material and components will flow in the process.

- Improving communication between sales and supply chain planning teams, which is also fundamental to asset velocity. Improved communication leads to better planning and coordination between suppliers and customers.

In effect, inventory that is not in motion creates friction, the opposite of flow. Inventory sitting still becomes a cash consumer instead of a cash producer. Shrinking the distance between factories, suppliers and customers reduces the time needed to move materials between them and the space between the nodes. Companies become leaner by removing waste from manufacturing and increasing the velocity of movement of goods between parties in the supply chain. In this sense, lean supply chains are interwoven with the laws of physics.

![]()

Barriers that prevent inventory from flowing naturally

When inventory gets bogged down, it stops moving altogether. In some cases, stock can sit for many years before being discovered and either sold as scrap or thrown away. There is an accounting term for this unfortunate state of affairs: excess inventory and obsolete materials. It is the scourge of many supply chain managers, and it is worthwhile to examine the reasons why it exists.

In a recent workshop at North Carolina State University, executives discussed why inventory flows were being shut down, which often resulted in stock being thrown away or sold at a discount, ultimately creating costs. Managers at this workshop came from many different industries, including the pharmaceutical, electronic, chemical, automotive and industrial sectors. No matter what context, all managers identified common reasons for why inventory stopped flowing over time. Slow-moving stock was often a by-product of misaligned decisions in areas such as product life cycles, design standardisation and promotional sales forecasting initiatives. It was common to find that the cost of excess inventory was often not measured effectively and therefore often ignored on balance sheets.

To prevent excess inventory write-offs, companies should document the individual components of inventory cost, including labour (warehouse management), damage, carrying cost, liability insurance, contractual obligation costs and other factors. The goal of doing so is not to drive accountability or blame but to ensure that everyone — including sales, manufacturing and purchasing/suppliers — is aware of the cost of poor inventory decisions.

Stock also piles up when a product is phased out or when a capital project concludes. Contractual commitments for holding inventory are often not well-defined, and the cost of customer commitments is often not factored into the sales account management cycle.

Every industry seems to have an inventory problem, which is often misunderstood and understated

When functional groups do not effectively work together to plan business cycles, inventory problems are sure to follow. Even within sales and operations, different locations may be buying the same materials but not sharing information. One division may have $10 million worth of stock on hand, while another is chasing down material to produce the same part.

Every industry seems to have an inventory problem, which is often misunderstood and understated. For example, a $4 billion company believed its total excess inventory was valued at $4 million. However, a study of the organisation discovered more than $44 million of surplus stock in its warehouses. Most of the business’s goods were obsolete, with stacks of 10-year-old materials that company executives did not even know were there.

Another problem, of course, is the misalignment that occurs during product planning cycles when forecasts are developed. Most organisations do not want to lose a sale, so inventory left over at the end of the quarter is often viewed as a mistake. When overstock occurs, it is frequently not acknowledged, and the decision on what to do with it is kicked forward into the future. Eventually, the sins of the company fall on the supply chain, and the excess inventory becomes the property of the supply chain team.

Businesses should examine and employ the approaches described above to promote increased velocity of their working capital inventory. Doing so may require significant changes in company mindset and culture but can produce important outcomes. First among these changes is eliminating the hoarding mentality of some executives, who feel uncomfortable if they are not sitting on a pile of inventory. Even during the supply chain shortages of 2021, companies had surplus stock: however, they were holding all the wrong types of materials, and not what customers were demanding!

PRACTICESHow does your industry and company define its supply chain scope of practice? |

PRINCIPLESWhat positions support a legal and ethical policy framework that will guide employees in the supply chain? |

PEOPLEWhat skills are required to support the company’s mission? |

|---|---|---|

PHILOSOPHYWhat approach to supply chain fits your organisation’s industry, culture, time, technology, capabilities and objectives? |

DESIGNING THE ORGANISATION TO INCREASE SUPPLY CHAIN VELOCITYCreating visibility is not enough by itself to drive velocity. Supply chain leaders need to define an operating environment that emphasises increased velocity. Tom Linton developed eight key questions that all supply chain leaders should consider when designing their organisation for improved flow and greater immunity. |

PHYSICSWhat structural requirements define the places, facilities and distances needed for efficient execution? |

PROCESSESHow will your company carry out its philosophies, policies and practices? |

POLICIESWhat rules are required to control organisational behaviour within the legal and ethical boundaries established by management? |

PERFORMANCEWhat types of objectives indicate success? Are they supported through agile decision-making? |

A supply chain immunity playbook

Here are some important lessons for readers to consider:

- Create indicators that provide early warning signals of both short-term problems and longer-term potential disruptions, and establish a governance structure for acting on these signals.

- Standardise parts, components and SKUs to create supply chain flexibility.

- Build deep knowledge of supplier and logistics capacity in a global supply chain.

- Invest in real-time event-tracking technologies with a dedicated response team.

- Weigh the cost of not investing when considering allocation of resources for supply chain immunity.

- Employ a flattened leadership structure to rapidly scale up a disaster response.

- Prioritise sourcing plans based on criticality.

- Leverage scale to support critical suppliers on tier-2 sourcing.

- Simplify contracting and negotiation to improve immunity.

- Ensure safety of all workers throughout the end-to-end supply chain.

Simplification of supply chain flows is a concept that has many important implications for how we design the supply chains of the future. In particular, the trade wars and COVID restrictions that brought supply chains to their knees are causing individuals to rethink the importance of flow.